ONCE MORE UNTO THE BREACH

Eugene O’Neill twice turned his troubled youth into all-absorbing drama. His family first appeared as a happy tangle of eccentric loved ones in Ah, Wilderness!, a halcyon 1933 comedy that revealed no greater family rifts than a generation gap and a father’s worry about his son’s preference for “decadent” poets. It was the happier side of a very ambivalent childhood.

Eight years later, exorcising old ghosts, O’Neill made them miserable in the well-named Long Day’s Journey into Night, a three-and-a-half-hour epic that chronicles an appropriately fogbound day which then sinks into a summer night without a smile. More a series of multiple exposures than conventional action, the “journey” consists of drugged or drunken confessions that create a kind of cumulative curse, with the characters defined as much by the lies they expose as the truths they conceal.

For O’Neill, this corrosive look at four loved ones who can’t make a move without hurting each other was never put on paper to be produced: O’Neill died in 1953. Three years later his widow, actress Carlotta Monterey, went against his wishes to withhold publication for 25 years after his death (after all, the family members who inspired the play were also now dead). The 1956 Broadway production may have secured a posthumous Tony and Pulitzer for the playwright, but was he right about letting sleeping scripts alone? Even as revivals have remained ubiquitous since then, should this extraordinarily talky, repetitive, meandering, character-study, four-act marathon of a maladjusted domicile never be staged?

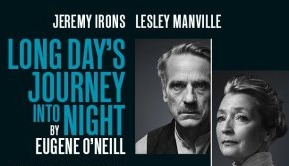

Of course it should be produced. It’s a significant drama of American hopes and disillusionment because O’Neill, like Williams but unlike Miller, looks to the family unit – not society — as passing down the misery of life, which is why the play is so relatable, profound and sad. But even as with Shakespeare’s wonkiest works, it comes down to acting and direction. And the Bristol Old Vic production starring Jeremy Irons and Lesley Manville has that in spades, yet its still short of electrifying.

Now a visiting production at The Wallis (by way of the West End and BAM in New York), director Richard Eyre knows how to trace the crumbs through a dark O’Neill forest, but he uses a flashlight when a fiery torch would have been more apropos. Still, the summer house of the Tyrone family festers with toxic believability: there’s the non-negotiable revelations about a father’s miserliness; a hophead mother’s return to virginal beginnings; a brother’s sabotage of his sibling; and the young son’s symbolic tuberculosis (called “consumption” here). With just one intermission, the first half fairly flies by at a clamoring clip, while the second is taken at a more somber and lumbering pace. That may make sense for the father’s 11 o’clock gloomy confession of regrets, but a horse shouldn’t trot at the end of the race.

It’s all enshrouded in Rob Howell’s enclosed set of glass walls that slice into the parlor like a coffin lid over the family’s dank and austere quarters. This translucency allows for some gorgeous and creepy moments of fog enshrouding the home, lit sepulchrally to chart the day’s progress by Peter Mumford. Unfortunately, it’s pure symbolism. With period furniture and a towering bookcase of unreachable height, it seems like a modern boutique hotel. It’s fascinating to look at but ultimately does nothing to enhance the play.

Best of all here is Ms. Manville (who received a well-deserved Oscar nomination this year for Phantom Thread): Devastating as mother Mary, whose slow surrender to morphine returns her to girlhood, she uses her supposedly pain-stricken hands to convey her toxic brew of loneliness, nostalgia and hopelessness (it’s really an excuse to take the narcotic originally prescribed by a cheap hotel doctor, hired by James when she was pregnant and on tour with him). For Mary, this summer house has never been a home and they’ve never been a family. With her snowy hair, surreptitious gesticulations and anxious giggles, Manville is the commonplace, uncomfortable housewife, progressively showing this capricious character’s caustic capacity as she unthinkingly rises up from her accumulative musings to scour the scars of both her scions and snoring spouse. Finally she attains a hypnotic disappearance act, vanishing into a realm of complete self-engrossment. That’s quite an achievement given the stagnant second half.

Because Mary embodies the play’s eventual elegy, it’s imperative that the father convey all the pent-up frustration of a pipe-dreamer gone sour. With a slight British accent suggesting a lifetime on the stage, Irons is more credible as a pitiful, sophisticated paterfamilias instead of a stalking, snarling, sneering, snapping survivor of all those cheap hotels and arduous travel from theater to theater. Though more passive than the role demands, Mr. Irons contrasts James’s peasant tenacity and stubborn stinginess with an unexpected lyricism as, between 8:30 a.m. and midnight on an August day in 1912, he confronts a lifetime of regrets.

Thin and intense, Matthew Beard plays the would-be poet Edmund, the author’s sickly surrogate, subtly with an almost feathery lightness, eschewing the crisp, bracing anger normally associated with the role. Irish actor Rory Keenan earns his excesses as older brother and wastrel Jamie, a boozing, womanizing, prodigal son who hates any success that could confirm his failure as an actor. Wisely, Keenan also drives home the brother’s need for love: Jamie’s later lacerations against Edmund seem almost selfless. As the Irish maid Cathleen, Jessica Regan offers amusement the play lacks. Cathleen won’t take nonsense but she has a post to uphold, and Regan navigates both sides of the small role quite well.

You may argue that a true dysfunctional family would never open up to each other as the Tyrones do; there would be sullen encounters, nasty but brief exchanges and mutual avoidance but no truth-telling. O’Neill, however, employs alcohol, morphine and the force of our own collective curiosity to unburden this Connecticut clan of seemingly unstoppable secrets. But the truth will never set them free.

Long Day’s Journey into Night

The Bristol Old Vic Production in association

with Fiery Angel and Pádraig Cusack

Bram Goldsmith Theater at The Wallis

9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd in Beverly Hills

ends on July 1, 2018

for tickets, call 310.746.4000 or visit The Wallis