MORE THAN JUST VARIATIONS ON A THEME

“Why did the great German composer Ludwig van Beethoven write 33 variations on a trivial little waltz by a mediocre amateur composer?” On the surface, the question itself may seem trivial, but playwright Moisés Kaufman expands the mystery of the 33 variations into a drama that makes us care. He explores the power of music, the ambiguity of history, the complex relations between a mother and daughter, the bravery and tragedy of fighting a fatal disease, and the many sides of friendship. So the scholarly problem of the variations question is just a narrative hook for this stimulating play presented by Actors Co-op in Hollywood.

Kaufman writes 33 Variations on two chronological levels. One takes place in the early 1800s with Beethoven in Bonn, Germany. The other is set today, as we follow an American music scholar named Katherine Brandt as she visits Bonn to examine archives that might hold the key to why Beethoven invested so much time and inspiration on the variations.

Kaufman writes 33 Variations on two chronological levels. One takes place in the early 1800s with Beethoven in Bonn, Germany. The other is set today, as we follow an American music scholar named Katherine Brandt as she visits Bonn to examine archives that might hold the key to why Beethoven invested so much time and inspiration on the variations.

Kaufman’s dramaturgy takes us into timeline-shifting Stoppard-esque territory, with separate stories played out simultaneously by characters unaware of each other’s presence, even speaking the same dialogue at the same time. As the story shuttles back and forth between today and the nineteenth century, the drama grows in narrative complexity to a poignant climax. While all these plot threads steam along, a pianist in full formal wear presides at a concert grand piano stage left, performing excerpts from the variations to suit the moods of the narratives.

Brandt has more on her plate than trying to solve the riddle of Beethoven’s variations. She faces a prickly relationship with her daughter Clara, an intelligent young woman who Katherine fears will be a mediocrity as a theater designer. More critically, Katherine is diagnosed with the incurable Lou Gehrig’s disease. Her life becomes a race against time as she tries to complete her Beethoven project before the disease overtakes her. Clara engages in a battle of wills with her stubborn mother over how to deal with the disease, but then the daughter’s life is unexpectedly complicated by an improbable romance with a male nurse named Mike who is involved in Katharine’s treatment.

We see Beethoven throwing himself into the variations, battling poverty and growing deafness and the importunities of his publisher Anton Diabelli, who composed the modest little waltz. Diabelli has signed up many of the great composers of the day to contribute a single variation on the waltz for a commemorative publication, and Beethoven’s interminable delays threaten the enterprise with dire financial consequences. But Beethoven won’t be hurried, bullying his friend and secretary Anton Schindler as well as the hapless Diabelli.

The play starts lightly, with Beethoven initially portrayed as a comical curmudgeon with whitening fright hair. But the density of the themes take hold in the second act. Katherine’s research into Beethoven’s variations is based heavily on written evidence left behind by Schindler, but that evidence may be bogus, suggesting the historical record is so unreliable as to be unusable. Katherine becomes close friends with a German woman named Gertrude Landenberger, a curator of the Beethoven archives who plays an increasingly intimate role in Katherine’s life that ultimately stretches their friendship to the breaking point. I’ve seen this show three times, and it seems odd that Katherine’s emotional trajectory with Gertrude is more complex and rich than that with her own daughter.

Kaufman is best known as the creator of two docudramas, The Laramie Project and Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, both of which persuasively take in hand the subject of homophobia. Kaufman based these works on actual people, but 33 Variations is only partly built on real-life individuals. Beethoven did employ a secretary named Anton Schindler, and Anton Diabelli was an actual Viennese music publisher who wrote the little waltz that triggered Beethoven’s burst of creativity, but the play’s stirring emotional confrontations and literate and witty dialogue come from Kaufman’s pen, not from a historical record. Kaufman deftly interweaves the stories separated by almost 200 years, and their unification at the end of the play is as logical as it is emotional.

Kaufman doesn’t write conventional plays. He constructs experiences which evolve through the special ingenuity of theatrical presentation. And he does that wonderfully here (in fact, there are 33 scenes, one for each variation). The character development of Beethoven, Schindler and Diabelli, however, is more successful than that of Brandt, a character lacking in humor and background. Even less successful is the creation of daughter Clara, who constantly fights her mother and who eventually is responsible for leading her into the light: Kaufman’s attempts to turn this strong-willed woman into a recognizable person never materialize.

Perhaps this is why director Thomas James O’Leary sometimes overplays the pathos here: The cast does fine work, but we could have used more quirkiness and humor to balance out the heaviness. Still, he has a sureness of touch that keeps the complex storytelling accessible and absorbing.

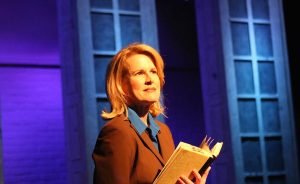

Nan McNamara is powerful as Brandt, an academic relentless in her pursuit of the truth behind the variations; in McNamara’s hands, she becomes a heartbreaking case history of a strong woman, her body destroyed by disease but not her spirit or dignity. Greyson Chadwick takes on the problematical role of Clara with sincere emotion; a likable Brandon Parrish plays Mike, the young man who initially seems underqualified for a woman of Clara’s intelligence and spunk (a dating scene with the two at a classical concert works particularly well). Complementing the modern side of the play is Treva Tegtmeier as Gertrude Landenberger, who blossoms from a no-nonsense minor figure in Katherine’s scholarly quest to a woman of compassion and steely strength.

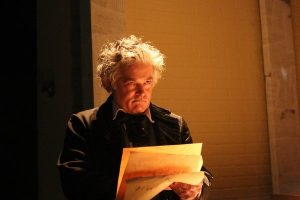

The performances are even better on the nineteenth century side. Bruce Ladd is an entertaining and ultimately wise and affecting Beethoven for all his bluster and irritability; Ladd illuminates Beethoven’s passion for his music in one effecting scene where he and the pianist join to feverishly dissect the musical components of the variations. Dylan Price is the impressive classical pianist who is onstage the entire performance. As Diabelli and Schindler respectively, Stephen Rockwell and John Allee both turn their characters—who are essentially comic foils for Beethoven—into three-dimensional ones.

Nicholas Acciani brings nineteenth century Bonn to life with his vivid projections and a puzzle-piece set that morphs from study rooms to a hospital to Beethoven’s home in seconds (aided greatly by Andrew Schmedake’s lights). Vicki Conrad designed the costumes, notably the authentic looking nineteenth century outfits for Diabelli and Schindler, and ratty ones for Beethoven.

33 Variations, despite its failure to make something honest and true of one of its pivotal characters, is an ultimately moving drama that manages to retain its cerebral underpinnings.

photos by Lindsay Schnebly

33 Variations

Actors Co-op

David Schall Theatre, 1760 N. Gower St.

(on the campus of the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood)

Fri & Sat at 8; Sun at 2:30; Sat at 2:30 (Feb. 18 & March 18 only)

ends on March 19, 2017 EXTENDED to March 26, 2017

for tickets, call 323.462.8460 or visit Actors Co-op