HARD TO CARE

First of all, I think it’s important to state that I adore The Flea, the fiercely creative performance and theater collective down in Soho. More often than not, they do amazing, compelling work. For instance, their two-night, epic presentation of The Mysteries last year, in which the Biblical story of creation through Armageddon was recounted by a troupe of about thirty writers and twenty performers, was one of the most wonderful, imaginative, and polished productions in New York or, indeed, anywhere. It was really startlingly brilliant, providing astonishingly innovative points of view of time-trodden stories and themes.

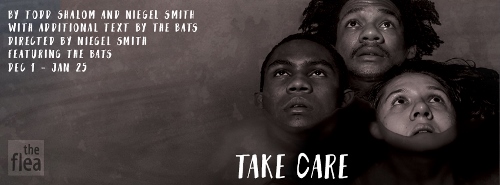

I wanted to make this point clear before I start this heady dis of Take Care, which is, quite frankly, simply dreadful – a tone deaf, unrelentingly shrill piece of immature agitprop which is the type of work that, I suppose, all 22-year-old aspiring writers must get out of themselves at some point. It’s just a pity that we have to be the ones subjected to it.

Upon arrival at the theater, one is told that this is “participatory” theater, meaning the audience is expected to work for it. This, in and of itself, isn’t the worst thing in the world: Although some of us are inevitably left a little uncomfortable by the sort of show in which the actors come out and pull your nose, insult you, and screech, there is a time and place for this kind of thing.

The box office staff actually offers you a “choice” for your participatory level: You can be either a full participant, a featured participant, or simply a voyeur. Unfortunately, though, at no point (until you have already made your choice and are seated in your audience chair) are you told what this means; it’s a little like when a tot asks you to promise not to get mad no matter what he tells you. How can you promise anything before you know what’s going on?

The box office staff actually offers you a “choice” for your participatory level: You can be either a full participant, a featured participant, or simply a voyeur. Unfortunately, though, at no point (until you have already made your choice and are seated in your audience chair) are you told what this means; it’s a little like when a tot asks you to promise not to get mad no matter what he tells you. How can you promise anything before you know what’s going on?

From the very start, though, the vibes are worrisome, as when the young lady at the coat check, a beautiful twenty-something lady who’s probably an NYU graduate and whose awareness of third world blight is watching the busboys at the coffeehouse at Parsons, snarks at you, “You can check your coat, you can check your bag, you can check your white privilege!” Oh dear: So that’s what we’re going to be in for, is it. I’m exhausted already.

I elected to be a “featured” participant, and, much to my alarm, I was handed a glass of water, a plastic poncho, and a big plastic bag containing a large bottle. I also was handed a two sheet flier, which had several stage directions written on it. At particular moments in the show, I was told to do whatever was in my script, timed to a gigantic LED timer that was hanging on the wall.

“Stand up and say ‘I don’t mind warm weather’” at 1 minute 30 seconds seemed easy enough, but I was a little more worried about a couple of the other directions, which included (at 20 minutes into the show) “Stand up, walk to the man standing on the center, spit on his shoes, and say ‘all lives matter!’” Later on, I am to round up all people of color and push them into the center of the stage. I swear to God, that’s what the script said. Other patrons had flyers on which were written different stage directions.

The ensemble of about 8 performers proceeded to enact a kaleidoscopic performance-art piece, seemingly arising from improvised elements about climate change and racism. The general theme appeared to be a sort of exploration of chaos and menace, and, incidentally, of the kind of casual cruelty that is arbitrarily and intentionally doled out by both nature and man.

The actors howl and yowl and roll around on the floor as a sort of storm hits the theater. Several audience members (those who had OK’d the idea of being “group” performers, poor souls, actually had to change into sweatpants and hoodies) sat on a tarp in the center of the room, while other actors poured water on their heads from jugs.

The actors howl and yowl and roll around on the floor as a sort of storm hits the theater. Several audience members (those who had OK’d the idea of being “group” performers, poor souls, actually had to change into sweatpants and hoodies) sat on a tarp in the center of the room, while other actors poured water on their heads from jugs.

During a scene of tremendous rage, actors ranged through the audience pelting people with water balloons, while a female performer squirted folks with a bloody syringe, noting “It only takes a little bit to kill you!” The fluid was cake batter, which is all right, I suppose, and because we were all wearing ponchos it was supposed to hit the plastic. However, in my case, and in the case of a few viewers nearby, the lady’s aim was not so good and, at least in my case, she entirely missed my poncho, instead covering my entire dry-clean only sweater and Brooks Brothers cotton-linen slacks with blood-red cake goo. I won’t send them the dry cleaning bill, as that would be unsporting, but I will give them this nice review instead.

When an African-American actor took to the center of the stage and pled for justice and mercy, it was the time for me to stand up and spit on his shoes, and I’m afraid I did. I really did not enjoy this very much. Elsewhere, actors sang a lovely song about the eye of a hurricane or something like that.

In one scene, an audience member won the right to sit in a plush seat in a gorgeous part of the theater as a door prize. Later, another participant was fitted with a gigantic, multi-colored Yma Sumac-like Mayan headpiece which was meant to represent the rainbow, and all the actors wriggled on the floor in front of her in ecstasy.

In one scene, an audience member won the right to sit in a plush seat in a gorgeous part of the theater as a door prize. Later, another participant was fitted with a gigantic, multi-colored Yma Sumac-like Mayan headpiece which was meant to represent the rainbow, and all the actors wriggled on the floor in front of her in ecstasy.

At the appointed time I was to have rounded up non-white patrons, I decided I no longer wanted to be a featured participant, so I simply didn’t step up to start bullying the audience members of color. To the credit of playwrights Niegel Smith (the Flea Artistic Director who also directed) and Todd Shalom, the production had allowed for the possibility of cowardly audience members: One of the bona fide actors stepped forward to do the round up. The ensuing skit was, as you may have expected, a metaphor for discriminatory, racist oppression.

The show’s pacing was commendably brisk and the atmosphere was indeed consistently surprising – even if this was the result of the show being randomly plotted and internally disjointed. The underlying messages the play was putting forward were commendable – but I question the relevance of them, given that if there was ever a case of playing to the choir, this show was it: I do not think there was a single person in the house who disagreed with a single element of the playwright’s increasingly shrill message, making us wonder why bother doing it at all. Maybe the play would have more impact in Oklahoma, but I daresay the farmers would just grab the actors, call them “brats”, and give them a good spanking.

More crucially, the ideologically empty show was essentially undone by the clumsy reliance on the audience participatory elements. The idea of audience participation in a show is really not one that should ever be taken lightly: In any experience, one must still look at things from the point of view of all the participants. When you force an audience member to do repellent things for no other reason than to make a heavy-handed point, you cannot really be said to understand what is going on in John Q. Public’s mind. Also, the participant must spend so much time worrying about what is coming up that it totally undercuts the ability to objectively enjoy or appreciate the play. But there was a sloppiness to the elements that suggested a lack of forethought, making the piece almost enraging – and not at the themes, but at the weak stagecraft.

poster photography by Eric McNatt

photos by Bjorn Bolinder

Take Care

The Bats at The Flea Theater

41 White Street in Tribeca

ends on January 25, 2016

for tickets, call 212-352-3101 or visit The Flea