THE HISTORY OF CINEMA IS A HISTORY OF US

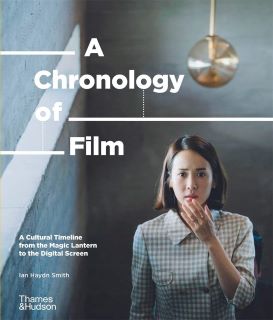

In A Chronology of Film, Ian Haydn Smith takes on the history of Cinema (and incidentally the history of the world) from the late nineteenth century to the present. As befits the recounting of a primarily visual medium, the book is a visual treat with a wealth of beautiful images. The posters, screen grabs and publicity stills are as important as the text, and vital to our understanding of the story he has to tell.

An Andalusian Dog (Un chien andalou, 1929), Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, France. Photo by Bunuel-Dali/Kobal/Shutterstock (5882285s)

And what a story! For far too many people, from serious students to casual fans, the history of film is simply the history of Hollywood. Smith disabuses us of that fallacy immediately; the book’s title page features that most international of stars Marlene Dietrich, in a pose combining old world decadence, new world panache, ambiguous sexuality and whatever else you wish to read into it. The introductory chapter then presents us with a series of German, British, Italian, Russian and yes, American images, reminding us that one of the great qualities of film as a medium is its accessibility; even in the days before air travel, a film made in Europe could be seen (with translated intertitles) in British and American cinemas in a matter of weeks, and vice versa. This ongoing cross-pollination was and still is one of the great strengths of the medium. Akira Kurosawa made The Seven Samurai in 1954, inspired by the Hollywood westerns he saw as a teenager in Tokyo, then in 1960 John Sturges remade it as The Magnificent Seven, bringing the story full circle to its western roots.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), William Cottrell, David Hand, Wilfred Jackson, Larry Morey, Perce Pearce and Ben Sharpsteen, USA Riccardo Bianchini / Alamy Stock Photo

Smith has created a timeline approach to his material which is ideal for the illustration of this cultural give-and-take. Alongside the cinematic images we are shown concurrent real-world history, reminding us that from its very beginnings film has reflected current events, and sometimes been ahead them. For example, in 1896 in Paris, Alice Guy-Blache became the world’s first female director, fifty years before Frenchwomen got the vote, and over a hundred years before Katherine Bigelow won her best director Oscar.

It Happened One Night (1934), Frank Capra, USA Angelo Hornak / Alamy Stock Photo

But first things first. Smith’s opening chapter takes us back to the beginning. Or rather, 30,000 years before the beginning, to a cave in France. A Paleolithic cave painting of galloping horses shows us maybe the earliest attempt to reproduce a sense of movement. From this extraordinary image we fast forward several thousand years to a succession of curiously-named optical inventions (Phenakiscope, anyone?) which attempt to solve the problem of visually simulating movement. The culmination of that search was seen in a Paris café on December 28, 1895 when Auguste and Louis Lumiere projected ten short films onto a public screen for the first time. In our media-sated times it’s almost impossible to imagine the heart-stopping (literally in some cases) impact these images must have had on that first audience. The fact that people fled from the room as a steam locomotive hurtled straight at them gives some idea of the reaction.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966), Sergio Leone, Italy A. Savin (Free Art License)

Within a few years of that event, it was discovered that by cutting separate shots together you could tell a story, paving the way for the narrative film as we know it today. Indeed, development was so rapid that within two decades, most of the film genres we recognize today were in existence; western (The Great Train Robbery, 1902), sci-fi fantasy (Le Voyage dans la Lune, 1902), historical epic (The Birth of a Nation, 1915). And in Cecil Hepworth’s Rescued by Rover (1905) we are introduced to the great-grand-daddy of Lassie, Rin Tin Tin and Benjy.

Charlie Chaplin, The Tramp (1915) Director: Charlie Chaplin. Photo by Essanay/Kobal/Shutterstock (5872239c)

By 1910 the American film community had relocated to Hollywood where it rapidly grew into a vast industry, making steady technical advancements through the teens and twenties. But it was Europe, particularly Germany, that led the way in artistic development with hugely ambitious experiments like The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari and Metropolis. America’s most significant contribution at this time was possibly the creation of the Star System. In the first decade of cinema actors were anonymous. Mostly from the legitimate stage, they considered film acting a come-down and preferred to remain anonymous. But before long it became apparent that some performers were more interesting than others and around 1910 Florence Lawrence became the first genuine movie star. She was also the object of the first publicity stunt, a bogus report of her death in a streetcar accident.

The Conformist (1970), Bernardo Bertolucci, Italy Philip Scalia / Alamy Stock Photo

The twenties brought silent cinema to a pitch of perfection throughout the world. Production values, performance and story-telling were at their zenith. Then in 1927 everything changed. The coming of sound brought the biggest upheaval to cinema since its inception and many of the painstakingly learned lessons of the previous thirty years had to be abandoned. Incorporating sound into such an essentially visual medium was a painful process and it was several years before picture and sound were successfully blended. For anyone suffering insomnia, I recommend pulling up any 1929 talkie on YouTube, you’ll be asleep in twenty minutes flat. However, the arrival of sound prompted an influx of new talent from the stage and saw the rise of several new genres, notably the musical and screwball comedy, where well-dressed New Yorkers downed endless martinis and traded witty insults. These lighter-than-air concoctions provided much-needed escape for audiences in the throes of the Depression.

Ashoka the Great (Aśoka, 2001), Santosh Sivan, India Sean Pavone / Alamy Stock Photo

Political events in Europe in the thirties resulted in another major cultural shift; most of the top cinematic talent of Germany left the country for France, England and especially America. Hollywood had already become something of a Mecca for European film makers (Sunrise, the last great American silent, was directed by the German F. W. Murnau in 1927). The influence of Europe on American cinema at this period was consequently vast, with many of the most important directors born outside the USA. This unprecedented influx of talent produced the correctly-named Golden Age of American cinema. As Hollywood attained a peak of technical expertise political events again took over and the world went to war. Hollywood fought the war on two fronts: patriotic propaganda encouraging us to support the war effort, and escapist entertainment encouraging us to forget it. Both genres produced some of the best films of the era. Casablanca can stand as representative of both types. In addition to being a summation of all the artistic and technical accomplishments of the time, it is both a superb romance and a highly successful piece of propaganda.

Psycho (1960), Alfred Hitchcock, USA Chiswick Chap (CC BY-SA 3.0); starring Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles and Martin Balsam. Hitchcock's masterpiece about a visit to the Bates Motel and Norman Bates peculiar relationship with his mother.

The historic and cinematic events of the second half of the twentieth and into our own century are equally well represented. Post-war nostalgia for a supposedly simpler time produced the great MGM musicals in America and lush, beautifully crafted period dramas such as The Earrings of Madame de… in Europe.

As the world emerged from six years of war, the cinema faced its biggest challenge yet – television. Smith vividly reports the various ways the film establishment met this challenge, sometimes successfully, often disastrously. Ultimately the two media formed the uneasy alliance which persists to this day.

Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi, 2001), Hayao Miyazaki, Japan Dietrich Burgmair / Alamy Stock Photo

By the mid-fifties, cozy nostalgia had given way to rebellion with the sudden appearance of teenagers (another American invention) with money in their pockets and zero interest in their parents’ values. This new audience led to the rise of the New Wave in Britain and France, defying censorship and addressing hitherto taboo subject matter. Ironically it was sixty-year-old Alfred Hitchcock who gave us the most New Wave movie of them all. In Psycho, he eschewed the high-gloss treatment of his fifties movies and returned to techniques he learned from German Expressionist cinema in the twenties, closing another artistic circle.

The world-wide breaking down of social and cultural barriers led to the counter-culture movies of the sixties and seventies, made by a new generation of film makers who are still with us. As the work of these artists evolved into mainstream entertainment the age of the blockbuster and the franchise was upon us, the “cinematic theme park” as Smith aptly terms it.

The Dark Knight (2008), Christopher Nolan, USA akg-images / Bildarchiv Monheim

Smith is a teacher, writer and broadcaster on film. His love of the art (and as he makes clear, it is an art, whether Federico Fellini or Ed Wood is in the driver’s seat) is apparent on every page of this delicious book. Its great strength, in addition to its meticulous research, is its reaffirmation of the way throughout its period, the times have shaped film and film has shaped the times.

And as he explains in his final chapter, the story never ends, and who knows what will happen next? For almost every zillion-dollar blockbuster hit (or flop) there is a low-budget surprise hit. The current cinematic scene is more diverse than it has ever been, and inspired by Haydn Smith, I can’t wait to see what happens next.

photos courtesy of Thames and Hudson

A CHRONOLOGY OF FILM: A CULTURAL TIMELINE AFROM THE MAGIC LANTERN TO NETFLIX

Thames & Hudson Inc.

Hardcover | 272 pages | 300 color illustrations | 8.8 in x 10.3 in x 1.1 in

available March 9th, 2021 at Amazon