COMPOSERS FORGOTTEN NO MORE

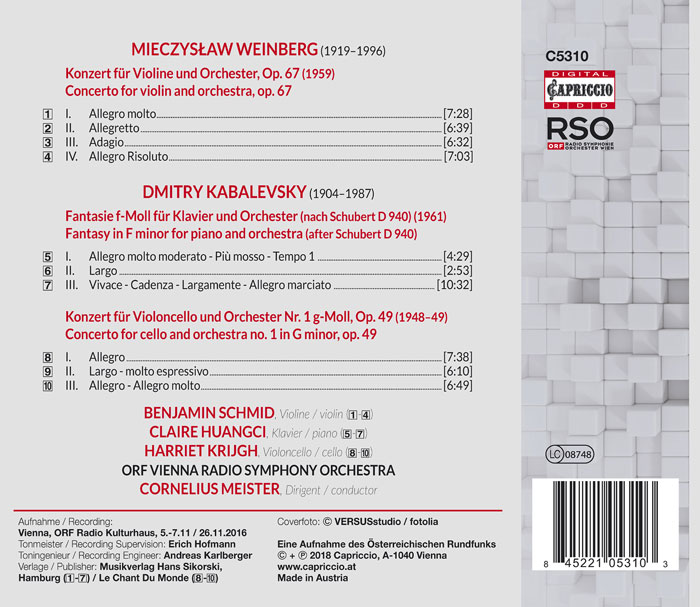

Immediately accessible and thrilling, the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSO) — under the exciting leadership of its Principal Conductor and Artistic Director Cornelius Meister — and three young soloists bring us lesser-known works by equally lesser-known composers who are finally finding themselves, decades after their deaths, edging their way into the popular repertoire.

It’s perfectly understandable but no less tragic that the name of composer Mieczysław Weinberg is practically unknown by classical enthusiasts, let alone the population at large (some spell and pronounce his name Vainberg). While many have never even heard of Weinberg (1919–1996), he was an extremely prolific author, with 26 symphonies, 7 operas, 17 string quartets, 19 sonatas, at least 150 songs, 7 operas and 2 ballets. He also created 65 film and animation scores, and musical scores for theater and radio shows.

But the Soviet-era composer didn’t fall into obscurity because of his oeuvre; the 20 or so pieces I’ve heard are fascinating, even as his beautiful works can be grim, sardonic and serious (which is logical given that most of his family was murdered by Nazis, while Weinberg was imprisoned by Soviet authorities — he fled Warsaw just in time and ended up staying in Moscow — and his father-in-law, the acclaimed actor Salomon Michoels, was murdered in 1948 on Joseph Stalin’s order).

Because he was a Soviet-era Polish Jew, the Soviets no doubt saw little reason to branch his music to the West; more important, he didn’t promote himself. Largely unknown outside of Russia until the last decade or so, the semi-modernist’s music is going through a Renaissance, due to players like the ever-adventurous 70-year-old violinist Gidon Kremer, and RSO, which has championed his works in concert halls and now on this magnificent recording of his Violin Concerto from the Capriccio label, which continues to fill the niches that other labels keep neglecting.

Also on this crystal-clear offering are two works by Dmitry Kabalevsky, a contemporary of Weinberg, who actually did play along with Soviet authorities. While he is unpopular and forgotten in some circles for being a Stalinist brown-noser, his Piano Fantasy and Cello Concerto No. 1 demand recognition.

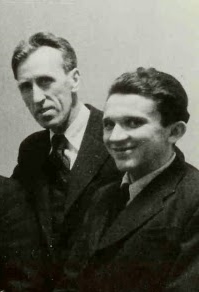

Contrary to urban legend, Weinberg was not a pupil of Shostakovich, but his confidante. 13 years younger than his more famous friend, Weinberg wrote, “Although I have never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood.” Their friendship was so close that it is believed that Weinberg is the source for Shostakovich’s interest in Jewish music. Shostakovich dedicated his String Quartet No.10 to Weinberg, and Weinberg dedicated his Symphony No.12 to Shostakovich in return.

Contrary to urban legend, Weinberg was not a pupil of Shostakovich, but his confidante. 13 years younger than his more famous friend, Weinberg wrote, “Although I have never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood.” Their friendship was so close that it is believed that Weinberg is the source for Shostakovich’s interest in Jewish music. Shostakovich dedicated his String Quartet No.10 to Weinberg, and Weinberg dedicated his Symphony No.12 to Shostakovich in return.

The Violin Concerto does not require dazzling melodrama and showmanship from the soloist, but probing, private expression (which comes unexpectedly after that crashing opening climax). Here, Benjamin Schmid (who has about 50 CDs under his belt), combines the soul of a village fiddler with the bravura of a concert hall virtuoso. With scorching scratches, his instincts are right on, giving us strength and searing passion. On equal footing with the thrilling Viennese violinist, the RSO attacked passages with brutal emotion.

The four movements aren’t easily pigeonholed — “modern” is too unspecific, and Shostakovichian is unfair. The first movement is pocked with tension, ever-building from the the incredibly fierce string section (the beefy bass section positively groans and growls). Parts of the second movement are sparse and very relaxing, gentle and elegant. The third moves like steady, soft ripples on water. The finale, an Allegro, starts with a militaristic march — aided by that exciting timpani — and ends with a warm lingering major pianissimo chord. This 1959 masterpiece contains the kind of accessibility that eludes most new music.

Representing Kabalevsky’s oeuvre of piano and orchestra music is an equally tuneful and reachable piece: A 1961 arrangement of Schubert’s Fantasy in F minor D 940 for piano four hands as a full-fledged piano concerto with an inserted cadenza in the finale. Transcribed for orchestra by others, Kabalevsky’s is by far the most efficacious, providing a fully modern orchestration without mimicking Schubert’s distinctive scoring style. The result is a delightful revelation of romantic rhapsody that is wholly successful as a singular piece of art unto itself, and a real find.

Based in Hannover, Germany, the 27-year old American pianist of Chinese descent, Claire Huangci — who has released two solo efforts on CD — gets her first symphonic recording here. And what a debut! Her exceptional focus, power and subtlety roam across the emotional landscape from extreme sensitivity to the most spirited enthusiasm. Additionally, the élan, meticulous mixing, and mastery of the escorting players add to the idyllic teamwork between motivated soloist and her backup.

Kabalevsky was very popular with Russian audiences, composing music that was pleasing to the ear, and did not stray far from convention. His three-movement Cello Concerto in G minor is pleasing from the first go-round, and is a real showcase for young up-and-coming cellist Harriet Krijgh, giving us her sixth recording with Capriccio. When the cello enters in the march-type Allegro, it’s with an arresting energetic melody that soars into the upper register. The opposing theme in this movement has less march and more of a lyrical quality. In a brief cadenza toward the end, Krijgh becomes more virtuosic, as ascending double stops and passagework in octaves create a thrilling acme that ends in a surprisingly low way.

The second movement is an elegiac, based on a melancholy Russian folk song, and the movement is structured so that the cello part plays several lyrical stanzas of the melody. The solo cadenza work is outstanding, leaving us the Allegro Molto, which contains contains many beautiful, expressive moments that are peppered with variations of the more agitated material from the opening. The cello part revs up even more than the first two movements, growing in intensity until very fast notes lead to a spirited close.

Jens F. Laurson’s liner notes are extraordinarily thorough, and — while a bit dismissive of Kabalevsky (whose music speaks for itself here) — often very humorous.

uncredited photo of Kabalevsky and Weinberg in Moscow, 1948

taken from the CD liner notes

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSO)

Cornelius Meister, conductor

Benjamin Schmid, violin; Claire Huangci, piano; Harriet Krijgh, cello

WEINBERG Violin Concerto | KABALEVSKY Fantasy; Cello Concerto No. 1

Capriccio C5310

10 tracks | 66:27

released January 5, 2018

available at Naxos and ArkivMusic