A LITTLE BLUE

More than a few friends recently mentioned that there are many “great” things on the boob tube. Since I don’t watch TV, it came as a surprise because I assumed it was mostly pablum. I was equally disturbed by this information not because I hold TV as mindless and addictive, but because it is I who have been experiencing the pablum lately – not on TV, but in the theater. Weak storytelling, poor construction, and static characters are hitting the boards from Broadway musicals to the latest LaBute or Mamet play.

Alongside that trend is that the running time of most new plays has been dwindling for a few years now. Not only do the vast majority of new plays rarely have an intermission, but they seem to be mostly clocking in at ninety minutes ON THE DOT. Yet, storytelling and construction is getting lazier and sloppier. Clearly, great theater is not a by-product of shorter plays (please save the “but there are some great plays being created today” speech for another time). I shudder when I hear people say, “Ninety minutes, no intermission? I love that!” As if the length of a theater piece excuses its mediocrity.

Obviously, if all of these new plays had the imagination, or quirky characters, or mind-bending perspectives of an average Pinter one-act, I’d be perfectly content. My point is that theater is packed with 22-minute stories stretched out to 90-minute one-act plays. Not even 90. In the last year, it’s astounding how many brand new plays are 60-75 minutes (but you’ll notice the price of theater is not abating along with the running time). And with Fringe Festivals becoming more popular, the average 1-hour piece may be the theater of the future. Is it possible that theater as we know it is quickly devolving before our eyes, threatening to become live television?

But what could this possibly have to do with the U.S. premiere of Athol Fugard’s The Blue Iris at the Fountain Theatre? Fugard is arguably one of our greatest living playwrights, incorporating into his enormous body of work themes of his anti-apartheid stance, interracial relationships, guilt, and mourning; occasionally, his plays are tinged with a flavor of Beckett or Brecht. Unlike his contemporary poetical dramatist August Wilson, whose ambitious—but often too-lengthy—plays tend to ebb-and-flow with bursts of terrifically explosive scenes, Fugard’s work tends to begin almost benignly and build to a shattering climax, as in Master Harold and the Boys.

At the height of apartheid, the writer’s plays were banned, and he was forced to produce his provocative works outside his native South Africa. Since the early 1960’s, Fugard, whose roots are both English and Afrikaner, has achieved world-wide recognition for his ability to refract the world’s political and social struggles into small two- and three-character dramas. Fugard lives part-time in Del Mar, but his prolific output normally begins in a tiny theater in South Africa’s Port Elizabeth, with Mr. Fugard often starring in and directing his plays. Since 2000, when he witnessed Stephen Sachs’ sterling production of The Road to Mecca at the Fountain, he has entrusted six of his plays to the intimate Los Angeles theater, including the 2010 U.S. premiere of The Train Driver, a devastating, poetic, haunting and beautiful journey into the world of one man’s inconsolable grief.

The main character in the two-person The Train Driver attempts to remedy his all-consuming trauma caused by the death of a black woman and her baby—the two faces he saw immediately before they were mutilated under the wheels of the train he was operating. He has searched villages to morgues—alienating his family and employer in the process—to locate the name of the woman. His travels bring him to the graveyard of a squatter camp where graves are covered in dusty dirt and rocks, with discarded junk serving as flowers. No one knows the names of the bodies at this makeshift cemetery, and a gravedigger must bury them deep so the dogs don’t dig them up at night to eat them.

Under Sachs’ directorial helm, not only was Driver a triumph of both technical design and acting normally associated with the Fountain, but the play contained an intelligible story with fleshed-out characters; even the gravedigger, who served more-or-less as a Greek chorus, was a multi-dimensional creation. (Under Fugard’s direction, New York’s Signature Theatre is opening The Train Driver this week, which also coincides with the playwright’s eightieth birthday.)

The Blue Iris is also about a man dealing with inconsolable grief. A lightning-strike has destroyed the home of a farmer in the semi-desert Karoo region of South Africa. Sifting through the charred debris with his black farm worker, the farmer mourns the death of his wife, who died of a “broken heart” after the blaze destroyed her life’s work—botanically accurate wildflower paintings. The housekeeper has kept hidden her feelings for the farmer, and urges him to abandon the blackened remains. A discovery of one of his wife’s untarnished watercolors—that of a blue iris which was painted during a drought—spurs his memories, which cause his wife to appear to him among the detritus. Now he must confront his guilt having left his shy, frightened wife alone in such a terrible storm.

It’s a fascinating story—equal parts ghost tale and memory play—and well-worth exploring. It’s amazing that at 80, Fugard still retains a remarkable knack for both human understanding and language (some of the dialogue is in Afrikaans, South Africa’s official language), and he shows no signs of slowing down his output. However, even with an extraordinary set-up and moments of Fugard’s customarily beautiful dialogue, the play feels like it fell into the trap of so much new theater, as though it was rushed to production before the script was completed.

Clocking in at under 70 minutes, the story is compelling but the storytelling is not; beautiful symbolism and metaphors abound, but they trump character development; and the chatty dialogue is lopsided with exposition and remembrances (indeed, the script is rife with “remember when you”-type dialogue). As with Fugard’s more than 30 other plays, Blue Iris is distinctly South African, but as it stands now, American audiences may not be as rapturous as the South African critics are toward the play, which is now receiving its South Africa premiere (a rolling production which moves to the Market Theatre in Johannesburg this week).

Morlan Higgins plays the farmer Robert, the man who refuses to leave his destroyed home. The actor moves with celerity between hostile anger and weepy sensitivity; his authenticity is so profound that you may feel the shame akin to eavesdropping on a conversation that you should not be privy to; he also delivers the Afrikaans dialect with amazing precision (dialect coach JB Blanc). I love how Fugard has Robert comb through the destroyed artifacts, searching not for items of worth, but for the ghost of his wife—Higgins displays that frustrated obsession in a performance which is a privilege to watch. Mr. Higgins is far and away my favorite actor in Los Angeles.

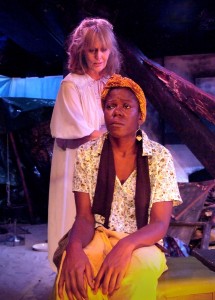

Julanne Chidi Hill makes an auspicious debut at the Fountain as Rieta, the farm worker for Robert and companion to his wife. Ms. Hill’s strength and earthiness are always evident; she is a captivating actress who is also a skilled listener; the only thing missing was a deep-seated sorrow, and a profound love for Robert—both of which would have rounded out her personal drama.

Jacqueline Schultz has the toughest job as Sally, who vacillates between a ghost who speaks directly to the characters on stage and a farmwife from years ago. Her range of emotions is breathtaking; she is loopy, lost, high-strung, and unpredictable.

Jacqueline Schultz has the toughest job as Sally, who vacillates between a ghost who speaks directly to the characters on stage and a farmwife from years ago. Her range of emotions is breathtaking; she is loopy, lost, high-strung, and unpredictable.

I’m open to the possibility that director Stephen Sachs did not discover a satisfactory arc for his players, for one of my issues is that the actors have nowhere to go: Ms. Hill starts off strong and aggressive, so there is no surprise when Rieta later reveals resentment and anger; Mr. Higgins begins stalwart, weepy and slightly addled, which he carries with him to the end, when he adds a bit of resignation; and Ms. Schultz’ consistent idiosyncrasies came with her and left with her, but I couldn’t quite get a handle on her character, wondering at times if she was simply bi-polar.

Being that this is a memory play, there seems to be a void when it comes to the love that the farmer shared with his wife; he says that he loved her, and copiously weeps at her absence, but I was aching for a flashback scene in which the wife is not a ghost, but a flesh-and-blood person whom her husband adores, thereby assisting the audience in mourning her loss as well. Another flashback would also serve as a chance for some much-needed emotion between the wife—who may or may not have loved her husband—and the young farm worker who did…and maybe still does.

Technically superior as always, the Fountain brought on set designer Jeff McLaughlin, whose detailed set of charred timbers and dusty floors enthralls; McLaughlin’s lights elegiacally evoke a twilight sky filtering in through the remains, but details such as lamplight still have a few kinks to work out. Naila Aladdin Sanders’ few costumes are marvelous: the frail material for the wife, and the tattered soiled work clothes of the husband are standouts. But it is Misty Carlisle’s work that must be recognized as a paragon of prop design, from the charred and bent brass headboard to the ruined watercolor paintings and shattered glass, Ms. Carlisle has achieved artistic status above and beyond the call of duty.

Athol Fugard isn’t capable of creating a mediocre play; it’s no wonder that only Shakespeare is produced more worldwide than Fugard. But The Blue Iris does need work in storytelling and construction; and while there is an inherent dimensionality to his characters, they are nonetheless stagnant. Because it has yet to be satisfactorily fleshed-out, Iris remains a 22-minute idea stretched-out to a 70-minute play (which felt much longer than that). Once the pieces are put in place, there is no reason why this play can’t make it to ninety minutes (maybe even on the dot) and regional houses around the globe.

photos by Ed Krieger

The Blue Iris

Fountain Theatre in Los Angeles

ends on September 16, 2012

for tickets, call 323 663-1525 or visit Fountain

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I think Beckett is produced more worldwide than Fugard.

It would be interesting to check that out.

Well, Alan, I have yet to find a RELIABLE source, but there is a toss-up between Alan Ayckbourn, Neil Simon, and Athol Fugard. I have yet to find ANY source citing Beckett.