THE GHOSTS OF GAMBLERS PAST AND PRESENT AND NO FUTURE

Someone once said that the only poet Los Angeles ever produced was Raymond Chandler. It must have been said before John Steppling came along. Steppling is the one playwright who has located the rot at the core of our city and its environs and who has found a myriad and seemingly infinite number of ways of defining and redefining just exactly what that rot is. He has never suggested that there is a cure. The logic is simple and irrefutable. There is no greater bullshit than the idea of The American Dream. We are all damned. Life goes on. The odds change. Dying is the one thing we’ve all got in common. His newest play – Phantom Luck – is a reminder that Steppling is willing to go closer to the edge of the precipice than practically any other Los Angeles playwright has ever gone. This is not just a play about gambling and death; it is to other plays what Verdi’s Requiem is to other requiems. It is a monumental – and I do not use that word loosely – ode to the chances people are willing to take even if – and probably because – they know that there are odds they simply cannot beat.  The tale of Anson and Jerry Dunn is true tragedy; it has been a long time since any playwright anywhere has attempted to look at two men and see in them the tragic failings of an entire culture. This is the era, after all, in which most translations of classic tragedies seem to turn them into domestic comedies, the better to keep the darkness at bay. If any play written in the past few decades demanded a production that was equal to the depth of its writing and its unrelenting curiosity about the fate that awaits us all, it is Phantom Luck. And it would be a shame if someone genuinely interested in theater didn’t take up its cause.

The tale of Anson and Jerry Dunn is true tragedy; it has been a long time since any playwright anywhere has attempted to look at two men and see in them the tragic failings of an entire culture. This is the era, after all, in which most translations of classic tragedies seem to turn them into domestic comedies, the better to keep the darkness at bay. If any play written in the past few decades demanded a production that was equal to the depth of its writing and its unrelenting curiosity about the fate that awaits us all, it is Phantom Luck. And it would be a shame if someone genuinely interested in theater didn’t take up its cause.

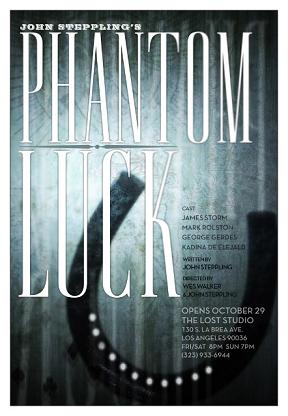

In the bare-bones, makeshift production – co-directed by Steppling and Wes Walker – which is being done at the Lost Studio, Phantom Luck is being heard more than seen. It might be enough, since what we hear is decidedly worth listening to. But it screams out for much more than that.

What we can do, under these circumstances, is to forget everything else and concentrate on the performances; here, for the most part, Phantom Luck has been dealt a winning hand. In everything George Gerdes (Anson) and James Storm (Dunn) do, there is such a remarkable combination of resignation and desperation that it is sometimes uncomfortably close to looking death in the face. Anson, the cancer-riddled gambler whose luck is almost always bad and is finally running out, realizes, with the help of his gambling buddy, Jerry Dunn, that the only way to beat the odds is to take the money and run. Is Dunn’s scheme a kind of wish fulfillment for Anson, and is he waiting, as it were, for his demise, and to play his own final hand on his own terms? Gerdes and Storm capture the shabby small-time angst of these men to a fare-thee-well, but they capture as well whatever nobility is left them on their journey to ruin and salvation. Gerdes and Storm get so under the skin of these characters that what they do is not like acting at all. Steppling has provided them with, quite simply, great parts, and they are paying him back by giving it all that they’ve got.

What we can do, under these circumstances, is to forget everything else and concentrate on the performances; here, for the most part, Phantom Luck has been dealt a winning hand. In everything George Gerdes (Anson) and James Storm (Dunn) do, there is such a remarkable combination of resignation and desperation that it is sometimes uncomfortably close to looking death in the face. Anson, the cancer-riddled gambler whose luck is almost always bad and is finally running out, realizes, with the help of his gambling buddy, Jerry Dunn, that the only way to beat the odds is to take the money and run. Is Dunn’s scheme a kind of wish fulfillment for Anson, and is he waiting, as it were, for his demise, and to play his own final hand on his own terms? Gerdes and Storm capture the shabby small-time angst of these men to a fare-thee-well, but they capture as well whatever nobility is left them on their journey to ruin and salvation. Gerdes and Storm get so under the skin of these characters that what they do is not like acting at all. Steppling has provided them with, quite simply, great parts, and they are paying him back by giving it all that they’ve got.

A third character, Johnny Cyr – a strutter in sharkskin with a tough veneer and an even tougher heart – is played crisply by Mark Rolston, who provides a nicely wrought and necessary lightness to the proceedings. There may be nothing funny in Steppling’s view of the world, but he knows how to inject a certain cockeyed balance to the tragedy at hand. And Rolston strikes that balance neatly.

A third character, Johnny Cyr – a strutter in sharkskin with a tough veneer and an even tougher heart – is played crisply by Mark Rolston, who provides a nicely wrought and necessary lightness to the proceedings. There may be nothing funny in Steppling’s view of the world, but he knows how to inject a certain cockeyed balance to the tragedy at hand. And Rolston strikes that balance neatly.

If the production were as pitch-perfect as these performances are, Steppling’s return to Los Angeles theater would be a major event of this season (or, for that matter, any season). But, alas, we’re still waiting for that production. There is absolutely nothing to look at that is visually arresting. In film noir, which Steppling’s plays frequently emulate, the play of light and shadow is crucial to the dramas that enfold; here, the look is flat and monotonous. It is hard to believe that the usually inventive Kathi O’Donohue is responsible for the inept lighting design. Another facet of film noir is the voice-over narration; here, suddenly, when the play is reaching its crescendo, Dunn’s voice is heard, as Dunn sits silently in dimness, and, though the concept is interesting, it is also, unfortunately, dramatically inert.  Another problem is the character of Anson’s woman, Josepha, who, in a fascinating bit of psychological symbolism, is always behind Anson, loving him without seeing anything but the back of his head and without him ever looking at her; this character never seems fully developed on a human scale, but her wisdom is Steppling’s, and she often says, mordantly and pithily, what is at the heart of the play. Unfortunately, Kadina De Elejalde, who plays the part, has no inner life whatsoever, and she delivers each line as if it were the Holy Grail; when everything a character says is of equal importance, it gets harder and harder, as the play progresses, to hear anything she says.

Another problem is the character of Anson’s woman, Josepha, who, in a fascinating bit of psychological symbolism, is always behind Anson, loving him without seeing anything but the back of his head and without him ever looking at her; this character never seems fully developed on a human scale, but her wisdom is Steppling’s, and she often says, mordantly and pithily, what is at the heart of the play. Unfortunately, Kadina De Elejalde, who plays the part, has no inner life whatsoever, and she delivers each line as if it were the Holy Grail; when everything a character says is of equal importance, it gets harder and harder, as the play progresses, to hear anything she says.

And, finally, at the performance this reviewer attended (after a rare Los Angeles rain), there was a leak in the ceiling of the Lost Studio and the drip was rather like a metronome, ticking away in counterpoint to the music of the play’s language which, in itself, was not uninteresting, and sometimes it sounded like a constant rain falling outside, which is not a bad metaphor for a Steppling play, but what could not be discounted was, either way, how singularly distracting it was.

And, finally, at the performance this reviewer attended (after a rare Los Angeles rain), there was a leak in the ceiling of the Lost Studio and the drip was rather like a metronome, ticking away in counterpoint to the music of the play’s language which, in itself, was not uninteresting, and sometimes it sounded like a constant rain falling outside, which is not a bad metaphor for a Steppling play, but what could not be discounted was, either way, how singularly distracting it was.

Steppling is a force and he needs to be taken seriously and treated seriously. It is almost certain that one day Phantom Luck will get the production it deserves. I had to wait more than half a century and sit through countless productions of The Glass Menagerie before I finally saw it fully realized. It would be good, however, for Steppling to be more fully appreciated in his own time. Phantom Luck is the right play at the right time. But it needs the kind of realization that is too often given these days to much lesser artists. That is one of the curses of our lazy contemporary theater.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Bonnie Perkinson

scheduled to close November 28 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://gunfighternation.tix.com/Schedule.asp?OrganizationNumber=3292

for more information, visit http://gfnation.wordpress.com/