A WONDROUS BUT TARNISHED OLD BOOK

While sitting through The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder, I had the feeling, both reassuring and discomforting, that this was not a new play, but rather the fragments of a play discovered in an attic somewhere in England, dusted off, and somehow stitched together, with a nod to contemporary re-think, into a new old play. What works is wondrous. And what doesn’t work is, well, pedantic (one doesn’t come up with a title like that and expect it not to be commented on).

No irony intended, but what doesn’t work is the contemporary re-think; Moby Pomerance, the sole author of this play (receiving its world premiere production at that jewel of a theater, Boston Court, in collaboration with the Circle X Theatre Company), seems to have jammed and stuffed modern attitudes into the play when a stodgily moribund found classic would have sufficed; would have, indeed, been welcome. When a play is about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary under the tutelage of Scottish lexicographer James Murray, one expects a torrent of words, like the packs of words that fill every bit of wall space – in Brian Sidney Bembridge’s splendid set – to overflowing, and, because language is what still separates the theater from most other media, we can relax and tread water gracefully when language comes at us with such eloquence and washes over us, until, of course, there are just too many words. And when, by “too many,” we mean the parts that get away from the intellectual pursuit of the play and which center, instead, on the relationships, then we are in trouble.

No irony intended, but what doesn’t work is the contemporary re-think; Moby Pomerance, the sole author of this play (receiving its world premiere production at that jewel of a theater, Boston Court, in collaboration with the Circle X Theatre Company), seems to have jammed and stuffed modern attitudes into the play when a stodgily moribund found classic would have sufficed; would have, indeed, been welcome. When a play is about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary under the tutelage of Scottish lexicographer James Murray, one expects a torrent of words, like the packs of words that fill every bit of wall space – in Brian Sidney Bembridge’s splendid set – to overflowing, and, because language is what still separates the theater from most other media, we can relax and tread water gracefully when language comes at us with such eloquence and washes over us, until, of course, there are just too many words. And when, by “too many,” we mean the parts that get away from the intellectual pursuit of the play and which center, instead, on the relationships, then we are in trouble.

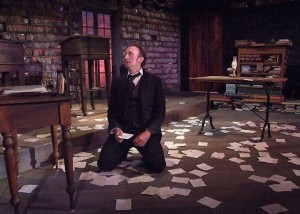

The odd thing is that the play reads beautifully: it is witty; its characters, at their best, are original creations; it seems to move swiftly; its theatrical possibilities are everywhere evident. It is easy to see why one would want to see this play staged. Furthermore, the production is, in many ways, impeccable. Bembridge’s aforementioned set is a thing of beauty; even before the play starts, one look at that set and we know how well it will adapt to a variety of settings, and Bembridge has lit it so that the shape and contours of every nook and cranny of his design is illuminated within an inch of its life. You’ve heard of leaving a theater and humming the scenery? Case in point. Dianne K. Graebner’s costumes, drab and pinched and period-perfect, have an eerily accurate sense of putting us into the world of the play (and could easily be used again if some unknown Russian play gets exhumed and cries out to be done). John Langs, who directed, is really good at creating stage pictures of comings and goings that have the verisimilitude of the way people really move and are, at the same time, visually and theatrically thrilling. The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder is stunning to look at; its look can keep us enthralled even during long arid stretches.

The odd thing is that the play reads beautifully: it is witty; its characters, at their best, are original creations; it seems to move swiftly; its theatrical possibilities are everywhere evident. It is easy to see why one would want to see this play staged. Furthermore, the production is, in many ways, impeccable. Bembridge’s aforementioned set is a thing of beauty; even before the play starts, one look at that set and we know how well it will adapt to a variety of settings, and Bembridge has lit it so that the shape and contours of every nook and cranny of his design is illuminated within an inch of its life. You’ve heard of leaving a theater and humming the scenery? Case in point. Dianne K. Graebner’s costumes, drab and pinched and period-perfect, have an eerily accurate sense of putting us into the world of the play (and could easily be used again if some unknown Russian play gets exhumed and cries out to be done). John Langs, who directed, is really good at creating stage pictures of comings and goings that have the verisimilitude of the way people really move and are, at the same time, visually and theatrically thrilling. The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder is stunning to look at; its look can keep us enthralled even during long arid stretches.

So where has it gone wrong? Well, for unknown reasons, instead of moving as elegantly as it should, it lurches forward, suddenly puts on the brakes, takes its time re-starting, and keeps going at that unwieldy pace for almost the entire length of its nearly three hours running time. The profusion of words becomes a jumble, bordering on incoherence. The wit is often sacrificed in favor of an image which, while interesting in and of itself, doesn’t really keep the play moving forward. Midway through the second act, one feels exhausted by the beauty of it, dulled by the humanity of it. The rivalry between Murray and his children, for example, explored fully if not deeply, seems to be more talked about than developed on stage. The absent-mindedness of Murray, which has a rich comic potential, disappears completely. The son’s homosexuality seems to have come, unannounced, from another play in another theater. There are moments, to be sure, to be savored: the reunion of brother and sister; the moment in which Smythic, Murray’s assistant, goes berserk and scatters words to the wind; those starling images of hustle and activity.

So where has it gone wrong? Well, for unknown reasons, instead of moving as elegantly as it should, it lurches forward, suddenly puts on the brakes, takes its time re-starting, and keeps going at that unwieldy pace for almost the entire length of its nearly three hours running time. The profusion of words becomes a jumble, bordering on incoherence. The wit is often sacrificed in favor of an image which, while interesting in and of itself, doesn’t really keep the play moving forward. Midway through the second act, one feels exhausted by the beauty of it, dulled by the humanity of it. The rivalry between Murray and his children, for example, explored fully if not deeply, seems to be more talked about than developed on stage. The absent-mindedness of Murray, which has a rich comic potential, disappears completely. The son’s homosexuality seems to have come, unannounced, from another play in another theater. There are moments, to be sure, to be savored: the reunion of brother and sister; the moment in which Smythic, Murray’s assistant, goes berserk and scatters words to the wind; those starling images of hustle and activity.

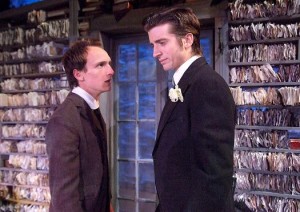

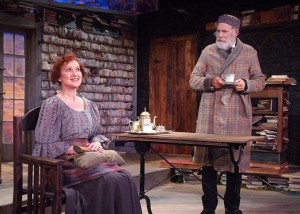

A good deal of the problem comes from the actors and the fact that Langs has not created a cohesive ensemble or, for that matter, concentrated diligently enough on the individual performances. John Getz is heartbreakingly humorless and embarrassingly one-dimensional as Murray; without a Scots burr – which might have defined his character –he barks and harumphs his way through the role and provides none of the characteristics ascribed to him by his children, so that their conflicts with him are lacking real contentiousness. Melanie Lora, who creates the evening’s most sustained performance – an authentic character study of a woman pushing for personal freedom through sheer will of purpose and intent – has, unfortunately, little to play against. Similarly, the other actor who finds the tone that is right for the play and for the beleaguered Smythic he portrays – Time Winters – works largely in a dramatic vacuum, fueled largely by his own manic energy. With most of the rest of the cast, one often wonders whether one is watching bad acting or valiant but failed efforts at style; in all fairness, each and every one of them gets at least one moment that is convincing and even riveting and so it would seem that the problem is either in the writing (which is only sometimes true) or the direction. It is Ryan Welsh, as Murray’s son, who suffers most from these weaknesses.

A good deal of the problem comes from the actors and the fact that Langs has not created a cohesive ensemble or, for that matter, concentrated diligently enough on the individual performances. John Getz is heartbreakingly humorless and embarrassingly one-dimensional as Murray; without a Scots burr – which might have defined his character –he barks and harumphs his way through the role and provides none of the characteristics ascribed to him by his children, so that their conflicts with him are lacking real contentiousness. Melanie Lora, who creates the evening’s most sustained performance – an authentic character study of a woman pushing for personal freedom through sheer will of purpose and intent – has, unfortunately, little to play against. Similarly, the other actor who finds the tone that is right for the play and for the beleaguered Smythic he portrays – Time Winters – works largely in a dramatic vacuum, fueled largely by his own manic energy. With most of the rest of the cast, one often wonders whether one is watching bad acting or valiant but failed efforts at style; in all fairness, each and every one of them gets at least one moment that is convincing and even riveting and so it would seem that the problem is either in the writing (which is only sometimes true) or the direction. It is Ryan Welsh, as Murray’s son, who suffers most from these weaknesses.

Then there is the matter of Henry Todd Ostendorf, who, in a double part, seems to have made no distinction between the two, and since Owen (the second of the two roles) leaves the job in the same way that Mr. Williams (the first of the two roles) does – in what seems like the exact same costume – it looks as if the play has taken a circular route and is starting all over again. It doesn’t help that the relationship between Owen and Murray’s son is so underdeveloped and so conveniently desexualized; it makes almost no impact whatsoever.

Then there is the matter of Henry Todd Ostendorf, who, in a double part, seems to have made no distinction between the two, and since Owen (the second of the two roles) leaves the job in the same way that Mr. Williams (the first of the two roles) does – in what seems like the exact same costume – it looks as if the play has taken a circular route and is starting all over again. It doesn’t help that the relationship between Owen and Murray’s son is so underdeveloped and so conveniently desexualized; it makes almost no impact whatsoever.

Pomerance is a promising writer; this play may even be the proper evidence of the fact, if it were done as written. Buts its longueurs and distractions and the sense that it often forgets its central subject – the creation of a dictionary – may, under any circumstances, prove a deterrent to ever getting it right. But this production of The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder, despite its array of arresting images and a host of fascinating subtexts, doesn‘t serve anyone very well.

Pomerance is a promising writer; this play may even be the proper evidence of the fact, if it were done as written. Buts its longueurs and distractions and the sense that it often forgets its central subject – the creation of a dictionary – may, under any circumstances, prove a deterrent to ever getting it right. But this production of The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder, despite its array of arresting images and a host of fascinating subtexts, doesn‘t serve anyone very well.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Ed Krieger

scheduled to end August 29 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.bostoncourt.com/events/61/the-good-book-of-pedantry-and-wonder

A WONDROUS BUT TARNISHED OLD BOOK

While sitting through The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder, I had the feeling, both reassuring and discomforting, that this was not a new play, but rather the fragments of a play discovered in an attic somewhere in England, dusted off, and somehow stitched together, with a nod to contemporary re-think, into a new old play. What works is wondrous. And what doesn’t work is, well, pedantic (one doesn’t come up with a title like that and expect it not to be commented on).

No irony intended, but what doesn’t work is the contemporary re-think; Moby Pomerance, the sole author of this play (receiving its world premiere production at that jewel of a theater, Boston Court, in collaboration with the Circle X Theatre Company), seems to have jammed and stuffed modern attitudes into the play when a stodgily moribund found classic would have sufficed; would have, indeed, been welcome. When a play is about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary under the tutelage of Scottish lexicographer James Murray, one expects a torrent of words, like the packs of words that fill every bit of wall space – in Brian Sidney Bembridge’s splendid set – to overflowing, and, because language is what still separates the theater from most other media, we can relax and tread water gracefully when language comes at us with such eloquence and washes over us, until, of course, there are just too many words. And when, by “too many,” we mean the parts that get away from the intellectual pursuit of the play and which center, instead, on the relationships, then we are in trouble.

The odd thing is that the play reads beautifully: it is witty; its characters, at their best, are original creations; it seems to move swiftly; its theatrical possibilities are everywhere evident. It is easy to see why one would want to see this play staged. Furthermore, the production is, in many ways, impeccable. Bembridge’s aforementioned set is a thing of beauty; even before the play starts, one look at that set and we know how well it will adapt to a variety of settings, and Bembridge has lit it so that the shape and contours of every nook and cranny of his design is illuminated within an inch of its life. You’ve heard of leaving a theater and humming the scenery? Case in point. Dianne K. Graebner’s costumes, drab and pinched and period-perfect, have an eerily accurate sense of putting us into the world of the play (and could easily be used again if some unknown Russian play gets exhumed and cries out to be done). John Langs, who directed, is really good at creating stage pictures of comings and goings that have the verisimilitude of the way people really move and are, at the same time, visually and theatrically thrilling. The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder is stunning to look at; its look can keep us enthralled even during long arid stretches.

So where has it gone wrong? Well, for unknown reasons, instead of moving as elegantly as it should, it lurches forward, suddenly puts on the brakes, takes its time re-starting, and keeps going at that unwieldy pace for almost the entire length of its nearly three hours running time. The profusion of words becomes a jumble, bordering on incoherence. The wit is often sacrificed in favor of an image which, while interesting in and of itself, doesn’t really keep the play moving forward. Midway through the second act, one feels exhausted by the beauty of it, dulled by the humanity of it. The rivalry between Murray and his children, for example, explored fully if not deeply, seems to be more talked about than developed on stage. The absent-mindedness of Murray, which has a rich comic potential, disappears completely. The son’s homosexuality seems to have come, unannounced, from another play in another theater. There are moments, to be sure, to be savored: the reunion of brother and sister; the moment in which Smythic, Murray’s assistant, goes berserk and scatters words to the wind; those starling images of hustle and activity.

A good deal of the problem comes from the actors and the fact that Langs has not created a cohesive ensemble or, for that matter, concentrated diligently enough on the individual performances. John Getz is heartbreakingly humorless and embarrassingly one-dimensional as Murray; without a Scots burr – which might have defined his character –he barks and harumphs his way through the role and provides none of the characteristics ascribed to him by his children, so that their conflicts with him are lacking real contentiousness. Melanie Lora, who creates the evening’s most sustained performance – an authentic character study of a woman pushing for personal freedom through sheer will of purpose and intent – has, unfortunately, little to play against. Similarly, the other actor who finds the tone that is right for the play and for the beleaguered Smythic he portrays – Time Winters – works largely in a dramatic vacuum, fueled largely by his own manic energy. With most of the rest of the cast, one often wonders whether one is watching bad acting or valiant but failed efforts at style; in all fairness, each and every one of them gets at least one moment that is convincing and even riveting and so it would seem that the problem is either in the writing (which is only sometimes true) or the direction. It is Ryan Welsh, as Murray’s son, who suffers most from these weaknesses.

Then there is the matter of Henry Todd Ostendorf, who, in a double part, seems to have made no distinction between the two, and since Owen (the second of the two roles) leaves the job in the same way that Mr. Williams (the first of the two roles) does – in what seems like the exact same costume – it looks as if the play has taken a circular route and is starting all over again. It doesn’t help that the relationship between Owen and Murray’s son is so underdeveloped and so conveniently desexualized; it makes almost no impact whatsoever.

Pomerance is a promising writer; this play may even be the proper evidence of the fact, if it were done as written. Buts its longueurs and distractions and the sense that it often forgets its central subject – the creation of a dictionary – may, under any circumstances, prove a deterrent to ever getting it right. But this production of The Good Book Of Pedantry And Wonder, despite its array of arresting images and a host of fascinating subtexts, doesn‘t serve anyone very well.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Ed Krieger

scheduled to end August 29 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.bostoncourt.com/events/61/the-good-book-of-pedantry-and-wonder