FOUND AND LOST AGAIN

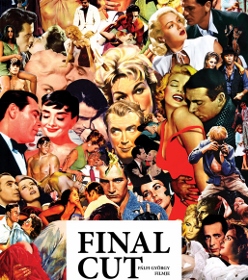

Formula movies can make you feel that you’ve already seen them. But György Pálfi’s latest film, which closed the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, is a love story so familiar that you have, in fact, sat through much of it before. Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen is a feature-length collage of clips from over 450 films: some classic, some obscure, some the most popular of all time. Each played by hundreds of actors shot over cinema’s century-plus, a man and woman fall in love; sexual rivals / the pressures of relationship and career / the vagaries of fortune intervene, but it’s all the old old story. Hundreds of directors and photographers tie this narrow cord into a neat bow, under the supervision of Mr. Pálfi and his editors (Judit Czakó, Károly Szalai, Nóra Richter, and Réka Lemhényi).

Formula movies can make you feel that you’ve already seen them. But György Pálfi’s latest film, which closed the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, is a love story so familiar that you have, in fact, sat through much of it before. Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen is a feature-length collage of clips from over 450 films: some classic, some obscure, some the most popular of all time. Each played by hundreds of actors shot over cinema’s century-plus, a man and woman fall in love; sexual rivals / the pressures of relationship and career / the vagaries of fortune intervene, but it’s all the old old story. Hundreds of directors and photographers tie this narrow cord into a neat bow, under the supervision of Mr. Pálfi and his editors (Judit Czakó, Károly Szalai, Nóra Richter, and Réka Lemhényi).

Leonardo DiCaprio may protest his passion to Sophia Loren; Jonathan Pryce can soar through the heavens after Greta Garbo’s kiss. Hitchcock may walk a man into a scene written by Dušan Makavejev, and James Cameron may fly a woman into Yasujiro Ozu’s house. It’s a fascinating and sometimes moving creation, an exercise more accessible than many in the found-footage movement, and at an equivalent measure perhaps less interesting to some academics and connoisseurs. There’s no denying the delight in juxtaposing Jack Lemmon’s and Tony Leung’s approach to the same acting problem, or in recognizing how Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini, and Tony Scott directed almost identical moments.

Leonardo DiCaprio may protest his passion to Sophia Loren; Jonathan Pryce can soar through the heavens after Greta Garbo’s kiss. Hitchcock may walk a man into a scene written by Dušan Makavejev, and James Cameron may fly a woman into Yasujiro Ozu’s house. It’s a fascinating and sometimes moving creation, an exercise more accessible than many in the found-footage movement, and at an equivalent measure perhaps less interesting to some academics and connoisseurs. There’s no denying the delight in juxtaposing Jack Lemmon’s and Tony Leung’s approach to the same acting problem, or in recognizing how Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini, and Tony Scott directed almost identical moments.

But from one perspective, by not really recontextualizing this footage but using it in its original boy-meets-girl storytelling function, Mr. Pálfi does little more than honor some of his favorite filmmakers and their habits. Sticking as closely as possible to existing archetypes of image and sound – can this be more than homage? And is three years’ editing time a fair trade for little more than a tribute? The result isn’t as  much fun as it might be, lacking a great deal of authorial voice; the viewer gets to know little about his director beyond an affection for a few movies in particular. But wait, is it Angel Heart he likes, or is it simply Mickey Rourke? Is it mere coincidence that in a movie like Angel Heart, director Alan Parker is playing with some of the same tropes that fascinate Mr. Pálfi? Does the slightly larger percentage of clips from a few movies reveal an artistic choice or a lazy palette? And the occasional ambiguity arising from actors in the right physical circumstance but playing an emotion not linear with that of the previous shot – is that intentional, or a momentary sacrifice of art to logistics?

much fun as it might be, lacking a great deal of authorial voice; the viewer gets to know little about his director beyond an affection for a few movies in particular. But wait, is it Angel Heart he likes, or is it simply Mickey Rourke? Is it mere coincidence that in a movie like Angel Heart, director Alan Parker is playing with some of the same tropes that fascinate Mr. Pálfi? Does the slightly larger percentage of clips from a few movies reveal an artistic choice or a lazy palette? And the occasional ambiguity arising from actors in the right physical circumstance but playing an emotion not linear with that of the previous shot – is that intentional, or a momentary sacrifice of art to logistics?

In the end, Final Cut seems largely to celebrate an idealized, rather shiny, not terribly personal vision of cinematic convention. It’s important to note that Mr. Pálfi has already made several very personal and unconventional narrative films of his own (Taxidermia generated a lot of interest in 2006), so his authorial restraint in  this film is no mistake. It’s a serious and fairly disciplined model of collage fillmmaking, and one of the few feature-length found footage pieces (although it’s brief compared to Christian Marclay’s 24-hour The Clock). There are few if any times when the narrative is unclear, a vital issue since traditional narrative is the theory under discussion. The editing is always appropriate and often clever in its choices, as when a series of ballroom dancing scenes culminates in the waltzing space station and shuttle from 2001: A Space Odyssey. But if the choice of image is not always surprising, and the story does get predictable at times, that might be part of the point.

this film is no mistake. It’s a serious and fairly disciplined model of collage fillmmaking, and one of the few feature-length found footage pieces (although it’s brief compared to Christian Marclay’s 24-hour The Clock). There are few if any times when the narrative is unclear, a vital issue since traditional narrative is the theory under discussion. The editing is always appropriate and often clever in its choices, as when a series of ballroom dancing scenes culminates in the waltzing space station and shuttle from 2001: A Space Odyssey. But if the choice of image is not always surprising, and the story does get predictable at times, that might be part of the point.

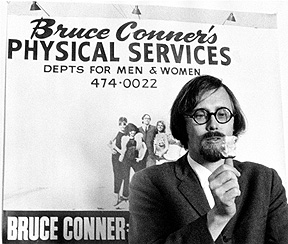

As points go, it may not be among the most stimulating. The late Bruce Conner used other people’s footage to explore questions of authorship studiously absent from Final Cut. Mr. Conner’s 1958 A MOVIE intercuts elephants with cowboy-and-Indian charges, subverting expectation in a manner perpendicular to Mr. Pálfi’s  intent; the 1963-4 REPORT explicitly challenges the viewer to explore his own role as a consumer in the larger society. Final Cut, on the other hand, assumes that its audience is in full agreement with a mainstream sensibility. By almost absolute contrast, Ron Rocheleau’s dadaist Concrete TV compilations investigate violent, pornographic popular culture and its relationship to political propaganda via Jungian models. It’s also undeniable that Mr. Rocheleau’s vocabulary of narrative film and television, of animation, of ephemera like industrial training films, of advertisements and music videos (and therefore his access to a finer brush), dwarfs the options within Mr. Pálfi’s self-imposed limitations.

intent; the 1963-4 REPORT explicitly challenges the viewer to explore his own role as a consumer in the larger society. Final Cut, on the other hand, assumes that its audience is in full agreement with a mainstream sensibility. By almost absolute contrast, Ron Rocheleau’s dadaist Concrete TV compilations investigate violent, pornographic popular culture and its relationship to political propaganda via Jungian models. It’s also undeniable that Mr. Rocheleau’s vocabulary of narrative film and television, of animation, of ephemera like industrial training films, of advertisements and music videos (and therefore his access to a finer brush), dwarfs the options within Mr. Pálfi’s self-imposed limitations.

With these points of comparison, it is tempting to accuse Mr. Pálfi of appealing to a safe, middlebrow international morality. But it’s hard to imagine a professional filmmaker making a movie out of copyrighted material owned by someone else and expecting to be able to sell it. Almost all found footage artists suffer this same constraint, that they will likely never enjoy commercial distribution because of the immense tangle of rights and ownership issues inherent to this type of movie. Recycling material and building on existing templates is not a concept new to art; Aristotle alludes to it in The Poetics. It is a concern for new artists, though, that as record companies and movie studios try to hedge their revenue bets against the new media, aggressive litigation is on the rise. One man’s fair use is another’s piracy.

With these points of comparison, it is tempting to accuse Mr. Pálfi of appealing to a safe, middlebrow international morality. But it’s hard to imagine a professional filmmaker making a movie out of copyrighted material owned by someone else and expecting to be able to sell it. Almost all found footage artists suffer this same constraint, that they will likely never enjoy commercial distribution because of the immense tangle of rights and ownership issues inherent to this type of movie. Recycling material and building on existing templates is not a concept new to art; Aristotle alludes to it in The Poetics. It is a concern for new artists, though, that as record companies and movie studios try to hedge their revenue bets against the new media, aggressive litigation is on the rise. One man’s fair use is another’s piracy.

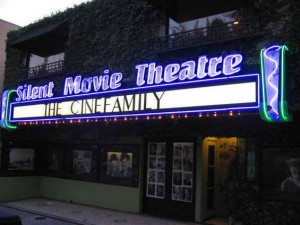

(That Final Cut got shown in Los Angeles at all, outside of festivals, is to the credit of the Cinefamily, a non-profit occupying the old Silent Movie Theatre across the street from Fairfax High School. Having hosted screenings of Bruce Conner, Mystery Science Theater 3000‘s Joel Hodgson, and other makers of found-footage, assemblage, and recycled film, the Cinefamily knew that this picture would not be  easily seen in America. So Head Programmer Hadrian Belove paid money to Wild Bunch, the movie’s European sales agent, and got the thing here in a near-exclusive showing. It might seem a risky investment, but he managed to sell a lot of tickets, too. The Cinefamily is able to show these objects of obscure desire to packed houses, successfully appealing to a niche market through a business model based on “donation” subscriptions. This private-club economy may come to define the distribution of art too legally actionable, too subversive, too experimental for mass consumption. Film consumers raised on the Internet are not all thieves; at least they seem to embrace alternatives to the multiplex model, and this must be regarded as a good thing.)

easily seen in America. So Head Programmer Hadrian Belove paid money to Wild Bunch, the movie’s European sales agent, and got the thing here in a near-exclusive showing. It might seem a risky investment, but he managed to sell a lot of tickets, too. The Cinefamily is able to show these objects of obscure desire to packed houses, successfully appealing to a niche market through a business model based on “donation” subscriptions. This private-club economy may come to define the distribution of art too legally actionable, too subversive, too experimental for mass consumption. Film consumers raised on the Internet are not all thieves; at least they seem to embrace alternatives to the multiplex model, and this must be regarded as a good thing.)

Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen

Wild Bunch International Sales

played October 4 – 8, 2013 at The Cinefamily

for Cinefamily programming information,

visit http://www.cinefamily.org