THE JOY OF TEARS

Having experienced 307 U.S. National Parks, I am keenly aware of the musical sounds of nature, such as the haunting accelerando of wind through pine needles, the drone of a bee, or the ever-changing sounds of water, as with bubbling staccato over stones, or a cascading scherzo down a ravine. Tan Dun masterfully replicates these sounds in The Tears of Nature, which is now receiving its U.S. premiere at Disney Hall. Not only does the fusion of Western and Eastern instruments successfully validate Dun’s ability to generate a wholly accessible work that expands the boundaries of conventional music, but the use of no less than 25 percussive implements serve as a showcase for one of the world’s preeminent percussionists, Martin Grubinger.

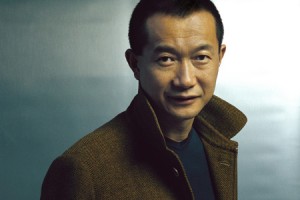

While Chinese composer Tan Dun is hardly a household name, movie audiences will certainly recognize his work from film (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero). He is well-known in the classical world for his cross-cultural compositions (operas, concertos, symphonies, oratorios, and more) which occasionally incorporate the use of non-traditional instruments with orchestra, heard in Water Passion after St. Matthew (2000), which utilizes 17 large transparent bowls of water, and Paper Concerto, commissioned by the LA Philharmonic for its world premiere at the opening of Disney Hall (2003), which relies solely on the handling of various paper-based items to create music. Dun is one of the few musical artists today who is successfully blurring the lines between old and new styles of music.

While Chinese composer Tan Dun is hardly a household name, movie audiences will certainly recognize his work from film (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero). He is well-known in the classical world for his cross-cultural compositions (operas, concertos, symphonies, oratorios, and more) which occasionally incorporate the use of non-traditional instruments with orchestra, heard in Water Passion after St. Matthew (2000), which utilizes 17 large transparent bowls of water, and Paper Concerto, commissioned by the LA Philharmonic for its world premiere at the opening of Disney Hall (2003), which relies solely on the handling of various paper-based items to create music. Dun is one of the few musical artists today who is successfully blurring the lines between old and new styles of music.

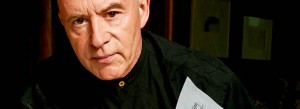

Conducted by the stately Christoph Eschenbach, the three-movement, 40-minute Tears of Nature demands to be seen, not just heard. The percussion concerto began as harpist Lou Anne Neill plucked a continuous musical phrase, followed by a euphoric Grubinger and the percussion section, who began tapping stones together. The orchestra made staggered entrances, after which instruments began communicating with each other. While tapping away, the Austria-based Grubinger – having memorized the piece – moved along the periphery of the orchestra, from down center to upstage, where he showed his prowess on 4 tympani, using mallets, sticks, brushes, and hands. At times, the strings would soar with an almost Copland-esque quality suggesting the jocundity in nature. Other times, the mood was perilous, ominous, and dramatic, as if to implicate man’s dubious relationship with the planet. Overall, the movement, which ended with Grubinger’s work on miniscule Chinese cymbals in tandem with the string section, evoked the awakening of a busy forest on a summer’s day which builds to a cacophony of activity.

The second movement, based on a Chinese folk song, was filled with pathos and poignancy. The violins would deliver a lush refrain, only to die away like a machine breaking down. The percussion section bowed on tiny Tibetan singing bowls throughout, creating an air of melancholy. At the center was the marimba, which not only lightened the mood, but highlighted Grubinger’s sizzling 4-mallet technique. Later in the third movement, Grubinger had a field day with both traditional and non-traditional percussion, changing mallets quicker than a magician’s sleight-of-hand. A long solo percussion section required the use of – among other devices – vibraphone, glockenspiel, rainstick, tom-toms, and nipple gongs (which resembled ornamental trash can lids). The dexterity displayed as Grubinger fluidly moved between instruments was astounding – although there was a tiny part of me which felt as though the music at this point was inspired more by Dun’s admiration of Grubinger’s skill and less about, per Dun, “the beautiful sadness of nature’s predicament and the threat to our survival today.” Still, the work is pastoral, inventive, affecting, exciting, and a resounding success.

The second movement, based on a Chinese folk song, was filled with pathos and poignancy. The violins would deliver a lush refrain, only to die away like a machine breaking down. The percussion section bowed on tiny Tibetan singing bowls throughout, creating an air of melancholy. At the center was the marimba, which not only lightened the mood, but highlighted Grubinger’s sizzling 4-mallet technique. Later in the third movement, Grubinger had a field day with both traditional and non-traditional percussion, changing mallets quicker than a magician’s sleight-of-hand. A long solo percussion section required the use of – among other devices – vibraphone, glockenspiel, rainstick, tom-toms, and nipple gongs (which resembled ornamental trash can lids). The dexterity displayed as Grubinger fluidly moved between instruments was astounding – although there was a tiny part of me which felt as though the music at this point was inspired more by Dun’s admiration of Grubinger’s skill and less about, per Dun, “the beautiful sadness of nature’s predicament and the threat to our survival today.” Still, the work is pastoral, inventive, affecting, exciting, and a resounding success.

As an encore, Grubinger displayed his expertise on a single marching drum, letting us know “this is not really music; it’s pure sport.” After his comical, clever, experimental and athletic performance on the drum, the audience went wild. Watching the young artist play live is a privilege, and this is a perfect way to introduce the Philharmonic to those unfamiliar with classical music.

Also on the program was the headliner: Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 (in F minor, Op. 36). It is no wonder that this is one of his most performed pieces, as it contains the romantic melodies associated with his work. But it is also highly dramatic, written in Italy just after the dissolution of his highly disastrous marriage (scholars debate that the work was inspired by his inability to proclaim his homosexuality).

There were impressive sections, most notably the Scherzo, in which the strings play pizzicato throughout. The precision was astonishing and there was an exhilarating sense of urgency. Interestingly enough, it was during this section that Eschenbach, who led from memory, put down his arms and conducted by jutting his head to and fro like a triumphant bird. Eschenbach seemed to intentionally pull back in other movements, which allowed the fundamental form of the symphony to speak for itself, but that also may have led to some restrained phrasing – which, of course, is a matter of taste, as in the Andante, which I prefer a bit less sluggish. As in his 2007 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, the German conductor took a more abstemious approach to the Symphony, but the reintroduction of the fanfare up to the end of the Finale was stunning.

There were impressive sections, most notably the Scherzo, in which the strings play pizzicato throughout. The precision was astonishing and there was an exhilarating sense of urgency. Interestingly enough, it was during this section that Eschenbach, who led from memory, put down his arms and conducted by jutting his head to and fro like a triumphant bird. Eschenbach seemed to intentionally pull back in other movements, which allowed the fundamental form of the symphony to speak for itself, but that also may have led to some restrained phrasing – which, of course, is a matter of taste, as in the Andante, which I prefer a bit less sluggish. As in his 2007 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, the German conductor took a more abstemious approach to the Symphony, but the reintroduction of the fanfare up to the end of the Finale was stunning.

While there was a robust, commanding sound from the string section – especially the cellos, led by the dynamic Tao Ni – and well-blended, virtuosic performances from the winds, the brass was sadly uneven. Not only did they lack that rich, piercing, crisp, powerful blare we associate with the work, but the opening fanfare was scratchy and weak, something which was difficult to recover from. The horns were smooth and sturdy, but they, too, faltered a few times. The magnificent acoustics at Disney Hall can magnify tiny mistakes; on the other side of that, you could clearly hear the piccolo and the triangle perfectly in the final movement, a rarity even on recordings.

The good news is that the Tchaikovsky is satisfying, but can get better in the final performances. The great news is that the Dun is terrific just as it is.

Eschenbach Conducts Tchaikovsky:

Dun / The Tears of Nature

Tchaikovsky / Symphony No. 4

Los Angeles Philharmonic at Walt Disney Concert Hall

ends on January 6, 2012

for tickets, call 323.850.2000 or visit http://www.laphil.com/

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Mr. Frankel,

You captured the Tan Dun piece perfectly. It was effective and affective for me also. It will be a joy to watch Grubinger become one of the best percussionists of his generation.

I also agree with your critique of the Tchaikosky Symphony. There were some rough moments in the brass section. I hope audiences on Saturday and Sunday got a better rendition of it!

The brass was sadly uneven? Scratchy and weak? Not from where I was sitting.