ACTS OF CONSCIENCE

All theater is inherently political, in that a story is only as objective as its teller. But some plays go straight to the 24 hour news cycle definition of politics, addressing problems of international diplomacy divisive enough that only a stage may politely host them. Sarah’s War, Valerie Dillman’s play enjoying its world premiere as the inaugural production of Freedom Theatre West, fulfills that new company’s mission to stage plays related to issues in the Middle East. An engaging drama by a promising playwright, well directed by Matt McKenzie, Sarah’s War has scenes of great beauty and passages of language so lovely that its occasionally awkward structure only mildly distracts from its overall quality.

The play was inspired by the life and death of American activist Rachel Corrie, who in 2003 was fatally injured by a bulldozer operating on behalf of the Israeli government. Corrie had taken a year off of college to protest the Israeli army’s razing of Palestinian homes in Gaza; her decision was even more inflammatory given Israel’s official position that the razed properties were harbors for terrorists in what has become the no-man’s-land between Hammas-dominated Gaza and Israel. Dillman has wisely renamed and fictionalized the central character and her family in order more freely to examine the circumstances of an act of conscience that created brief headlines for newspapers but permanent nightmares for friends and family of what some would call a victim, others term a freedom fighter, and still others dismiss as an idealistic pawn.

Presented in a style that fragments chronology and reality, not always to dramatic or thematic benefit, Sarah’s War offers moments before, during and after Sarah’s (Abica Dubay) fatal journey. Conflict unifies the disparate action: every character in this story fights with everyone else. Sarah, unlike Rachel Corrie, is Jewish, and so her trip creates rifts in her family even before she gets on a plane. Her uncle and aunt (Allan Wasserman and Ann Bronston) disagree about whether to fund her travel; her mother and father (Terry Davis and Lindsey Ginter) bicker over their own marital issues and over Sarah’s independence; Sarah’s sister (played at the performance I saw by the playwright) fights with her mother about not being the favorite daughter, and with her father about the defensibility of Sarah’s actions.

Even Sarah argues with a fellow activist (Marley McClean) over her own comportment, and with her Palestinian host family’s daughter (Dina Simon) about the viability of her mission. A translator (Ayman Samman) fights with that daughter, too. Everybody fights, and about what, in the end? Every character except Sarah is suffused with the weariness of extended struggle. So do we choose our battles, and is it okay to lose as long as we’re fighting a good fight? These are the questions this play asks, in scenes written and performed with delicacy and intelligence. They all reveal much about the politics of inclusion, loyalty and conscience. Director and writer mostly steer clear of assigning blame or taking sides in these conflicts, choices that serve the play and the production well.

Potentially elevating the stakes of the proceedings, Dillman introduces Danny (Will Rothhaar), a conflicted Israeli soldier who plays an instrumental role in Sarah’s fate. Danny wrangles with his friend Avi (played at the performance I saw by the versatile Ryan Martin) and with his commanding officer (Avner Garbi) over his responsibilities to his nation and to his beliefs. While this character’s arc could add much to the complexity of the play, Dillman has not quite explored his range of possibilities, and a fantasy scene presented in denouement only clutters the play’s already busy landscape of ideas.

More problematic are the multiple soliloquies delivered by every major character, divulgences that sometimes shed light on intentions but nearly always would have been more interesting and powerful if they had been delivered to another onstage character. I asked Dillman about the choice, and she said she simply liked what she called the theatricality of the device. I would argue that there is less theatricality in a person making a speech than in two people talking. True, the soliloquy exists for a reason, to engage the audience directly in an intimate and potentially confrontational manner. But, overused, the trick robs itself of novelty and impact.

Director McKenzie keeps the action moving, but is hampered by a reliance on digital projection (by Keith Stevenson) that has an effect on the production directly opposite to its intentions. Technology only assists theatricality a) when it works and b) when it’s used theatrically. To use a projection of a starry sky to suggest night, or a picture of trees to suggest a park, is to cheat the audience of your skills as a director in bringing these locales to life in a truly theatrical manner. Many a production of Zoo Story has managed, in a black box, to conjure Central Park without the aid of a Macbook. And when your technical facilities are limited to a laptop program that must be restarted when the director yells “Start over!” from the house, the questionable nature of your reliance on technology becomes clear. On this note, William Wilday’s lighting scheme leaves a dark hole upstage center, an error which leaves several actors in the dark. This bright play, and this mostly fine production, deserves better.

photos by Jordan Elgrably and John P Flynn

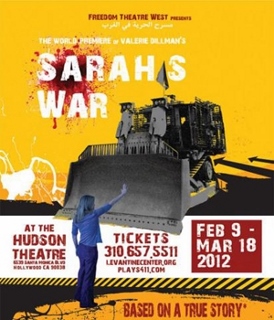

Sarah’s War

Freedom Theatre West

Hudson Mainstage Theatre

6539 Santa Monica Blvd in Hollywood

ends on March 18, 2012 EXTENDED to April 15, 2012

for tickets, visit Plays 411

for show info, visit Freedom Theatre West